| Part of a series on the |

| Catholic Church |

|---|

|

| Organisation |

| Background |

| Theology |

| Liturgy and worship |

| Rites |

| Criticism and controversies |

| Other topics |

| Catholicism portal |

The Catholic Church teaches that it is the one true church founded by Jesus Christ,[4][note 1] that its bishops are the successors of Christ's apostles, and that the Pope is the successor to Saint Peter.[5] The Church maintains that the doctrine on faith and morals that it presents as definitive is infallible.[6][note 2] The Latin Church, the autonomous Eastern Catholic Churches and religious communities such as the Jesuits, mendicant orders and enclosed monastic orders reflect the variety of theological emphases within the Church.[7][8]

The sacraments are integral to Catholic liturgical worship.[9] The principal sacrament is the Eucharist, also called the Mass. The Church teaches that in this sacrament the bread and the wine consecrated by the priest become the body and the blood of Christ, a change it calls transubstantiation.[10] The Catholic Church practises closed communion and only baptised members deemed to be in a state of grace, free of unforgiven mortal sin or penalty, are ordinarily permitted to receive the Eucharist.[11]

The Church venerates Mary. This veneration is called hyperdulia and is distinct from the worship, or latria, due by justice to God alone.[12] All of the Church's Mariology hinges on her title Mother of God. The Church teaches that her motherhood came about through divine intervention and she gave birth to him while still a virgin. It has defined four specific Marian dogmatic teachings: her Immaculate Conception without original sin, her status as the Mother of God,[13] her perpetual virginity and her bodily Assumption into Heaven at the end of her earthly life.[14] Numerous Marian devotions are also practised.

The Catholic social teaching emphasises support for the sick, the poor and the afflicted through the corporal works of mercy and the Catholic Church is the largest non-government provider of education and medical services in the world.[15] Catholic spiritual teaching emphasises spread of the Gospel message and spiritual works of mercy. In recent decades, the Catholic Church has been criticised for its doctrines concerning sexual issues and the ordination of women as well as for its handling of sexual abuse cases.

Name[edit]

Further information: Roman Catholic (term) and History of the term "Catholic"

Catholic was first used to describe the Christian church in the early 2nd century.[17] The first known use of the phrase "the catholic church" (he katholike ekklesia) occurred in the letter from St Ignatius to the Smyrnaeans, written about 110 AD.[note 3] In the Catechetical Discourses of St. Cyril of Jerusalem, the name "Catholic Church" is used to distinguish it from other groups that also call themselves the Church.[18][19]

Since the East–West Schism of 1054, the Eastern Church has taken the adjective "Orthodox" as its distinctive epithet, and the Western Church in communion with the Holy See has similarly taken "Catholic", keeping that description also after the 16th-century Reformation, when those that ceased to be in communion became known as Protestants.[20][21]

The name "Catholic Church" is the most common designation used in official church documents.[22] It is also the name which Pope Paul VI used when signing documents of the Second Vatican Council.[23] However, documents produced both by the Holy See[note 4] and by certain national episcopal conferences[note 5] occasionally refer to the Church as the Roman Catholic Church. The Catechism of Pope Pius X, published in 1908, also used the term "Roman" to distinguish the Catholic Church from other Christian communities who are not in full communion with the Holy See.[24]

Organisation and demographics[edit]

| Catholic Church |

|---|

| Major sui iuris Churches Listed by liturgical rite |

| Western traditions |

| Latin Church |

| Byzantine tradition |

| Albanian Church • Belarusian Church Bulgarian Church Church of Croatia, Serbia and Montenegro Byzantine Church • Hungarian Church Italo-Albanian Catholic Church • Macedonian Church Melkite Church • Romanian Church Russian Church • Ruthenian Church Slovak Church • Ukrainian Church |

| Antiochian or West Syrian tradition |

| Maronite Church • Syriac Church Syro-Malankara Church |

| Chaldean or East Syrian tradition |

| Chaldean Church • Syro-Malabar Church |

| Armenian tradition |

| Armenian Church |

| Alexandrian tradition |

| Coptic Church • Ethiopian Church Eritrean Church |

| Catholicism portal |

Papacy and Roman Curia[edit]

Main article: Hierarchy of the Catholic Church

Further information: Pope and List of popes

The office of the Pope is known as the papacy. The Catholic Church holds that Christ instituted the papacy upon giving the keys of Heaven to Saint Peter. His ecclesiastical jurisdiction is called the "Holy See" (Sancta Sedes in Latin), or the "Apostolic See" (meaning the see of the apostle Peter).[27][28] Directly serving the Pope is the Roman Curia, the central governing body that administers the day-to-day business of the Catholic Church. The Pope is also Sovereign of Vatican City State,[29] a small city-state entirely enclaved within the city of Rome, which is an entity distinct from the Holy See. It is as head of the Holy See, not as head of Vatican City State, that the Pope receives ambassadors of states and sends them his own diplomatic representatives.[30]

The position of cardinal is a rank of honour bestowed by popes on certain clergy, such as leaders within the Roman Curia, bishops serving in major cities and distinguished theologians. For advice and assistance in governing, the pope may turn to the College of Cardinals.[31]

Following the death or resignation of a pope,[note 6] members of the College of Cardinals who are under age 80 meet in a papal conclave to elect a successor.[32] Although the conclave may elect any male Catholic as Pope, since 1389 only cardinals have been elected.[33]

Canon law[edit]

Main article: Canon law (Catholic Church)

The canon law of the Catholic Church is the system of laws and legal principles made and enforced by the hierarchical authorities to regulate the church's external organisation and government and to order and direct the activities of Catholics towards the church's mission.[34] In the Catholic Church, universal positive ecclesiastical laws, based upon either immutable divine and natural law, or changeable circumstantial and merely positive law, derive formal authority and promulgation from the office of pope who, as Supreme Pontiff, possesses the totality of legislative, executive and judicial power in his person.[35] It has all the ordinary elements of a mature legal system:[36] laws, courts, lawyers, judges,[36] a fully articulated legal code,[37] principles of legal interpretation[38] and coercive penalties that are limited to moral coercion.[39][40]Canon law concerns the Catholic Church's life and organisation and is distinct from civil law. In its own field it gives force to civil law only by specific enactment in matters such as the guardianship of minors.[41] Similarly, civil law may give force in its field to canon law, but only by specific enactment, as with regard to canonical marriages.[42] Currently, the 1983 Code of Canon Law is in effect primarily for the Latin Church.[43] The distinct 1990 Code of Canons for the Eastern Churches (CCEO, after the Latin initials) applies to the autonomous Eastern Catholic Churches.[44]

Autonomous particular churches[edit]

Main articles: Latin Church and Eastern Catholic Churches

The Catholic Church is made up of 24 autonomous particular churches, each of which accepts the supreme authority of the Bishop of Rome on matters of doctrine.[45][46] These churches, also known by the Latin term sui iuris churches, are communities of Catholic Christians whose forms of worship reflect different historical and cultural influences rather than differences in doctrine. In general, each sui iuris church is headed by a patriarch or high-ranking bishop,[47] and has a degree of self-governance over the particulars of its internal organisation, liturgical rites, liturgical calendar and other aspects of its spirituality.[48]The largest by far of the particular churches is the Latin Church, which reports over one billion members. It developed in southern Europe and North Africa. Then it spread throughout Western, Central and Northern Europe, before expanding to the rest of the world. The Latin Church is part of Western Christianity, a heritage of certain beliefs and customs originating in various European countries, some of which are inherited by many Christian denominations that trace their origins to the Protestant Reformation.[49]

Relatively small in terms of adherents compared to the Latin Church, but important to the overall structure of the Church, are the 23 self-governing Eastern Catholic Churches with a combined membership of 17.3 million as of 2010.[50] The Eastern Catholic Churches follow the traditions and spirituality of Eastern Christianity and are composed of Eastern Christians who have always remained in full communion with the Catholic Church or who have chosen to reenter full communion in the centuries following the East–West Schism and earlier divisions. Some Eastern Catholic Churches are governed by a patriarch who is elected by the synod of the bishops of that church,[51] others are headed by a major archbishop,[52] others are under a metropolitan,[53] and others are organised as individual eparchies.[54] The Roman Curia has a specific department, the Congregation for the Oriental Churches, to maintain relations with them.[55]

Dioceses, parishes, and religious orders[edit]

See also: Catholic Church § Ordination and § Women and ordination

Countries by number of Catholics in 2010.[56]

More than 100 million

More than 50 million

More than 20 million

More than 10 million

More than 5 million

More than 1 million

Dioceses are divided into parishes, each with one or more priests, deacons or lay ecclesial ministers.[59] Parishes are responsible for the day to day celebration of the sacraments and pastoral care of the laity.[60]

In the Latin Church, Catholic men may serve as deacons or priests by receiving sacramental ordination. Men and women may serve as extraordinary ministers of Holy Communion, as readers (lectors); or as altar servers. Historically, boys and men have only been permitted to serve as altar servers; however since the 1990s, girls and women have also been permitted.[61][note 7]

Ordained Catholics, as well as members of the laity, may enter into consecrated life either on an individual basis, as a hermit or consecrated virgin, or by joining an institute of consecrated life (a religious institute or a secular institute) in which to take vows confirming their desire to follow the three evangelical counsels of chastity, poverty and obedience.[62] Examples of institutes of consecrated life are the Benedictines, the Carmelites, the Dominicans, the Franciscans, the Missionaries of Charity, the Legionaries of Christ and the Sisters of Mercy.[62]

"Religious institutes" is a modern term encompassing both "religious orders" and "religious congregations" which were once distinguished in Canon Law.[63] The terms "Religious order" and "religious institute" tend to be used as synonyms colloquially.[64]

Membership statistics[edit]

Main article: Catholicism by country

Further information: List of Christian denominations by number of members

Church membership in 2011 was 1.214 billion (17.5% of the world population),[1] an increase from 437 million in 1950[65] and 654 million in 1970.[66] Since 2010, the rate of increase was 1.5% with a 2.3% increase in Africa and a 0.3% increase in the Americas and Europe. 48.8% of Catholics live in the Americas, 23.5% in Europe, 16.0% in Africa, 10.9% in Asia and 0.8% in Oceania.[1] Catholics represent about half of all Christians.[67]In 2011, the Church had 413,418 priests. The main growth areas have been Asia and Africa with 39% and 32% increases respectively since 2000, while the numbers were steady in the Americas and dropped by 9% in Europe.[1] In 2006, members of consecrated life totalled 945,210; 743,200 of whom were female.[68]

Doctrine[edit]

Catholic doctrine has developed over the centuries, reflecting direct teachings of early Christians, formal definitions of heretical and orthodox beliefs by ecumenical councils and in papal bulls, and theological debate by scholars. The Church believes that it is continually guided by the Holy Spirit as it discerns new theological issues and is protected infallibly from falling into doctrinal error when a firm decision on an issue is reached.[69][70]It teaches that revelation has one common source, God, and two distinct modes of transmission: Sacred Scripture and Sacred Tradition,[71][72] and that these are authentically interpreted by the Magisterium.[73][74] Sacred Scripture consists of the 73 books of the Catholic Bible, consisting of 46 Old Testament and 27 New Testament writings. The New Testament books are accepted by Christians of both East and West, however some Protestants place them at three different status levels.[note 8] The Old Testament books include some, referred to as Deuterocanonical, that Protestants exclude but that Eastern Christians too regard as part of the Bible.[75] Sacred Tradition consists of those teachings believed by the Church to have been handed down since the time of the Apostles.[76] Sacred Scripture and Sacred Tradition are collectively known as the "deposit of faith" (depositum fidei). These are in turn interpreted by the Magisterium (from magister, Latin for "teacher"), the Church's teaching authority, which is exercised by the Pope and the College of Bishops in union with the Pope, the bishop of Rome.[77] Catholic doctrine is authoritatively summarised in the Catechism of the Catholic Church, published by the Holy See.[78][79]

Nature of God[edit]

Traditional graphic representation of the Trinity: The earliest attested version of the diagram, from a manuscript of Peter of Poitiers' writings, c. 1210

Catholics believe that Jesus Christ is the Second Person of the Trinity, God the Son. In an event known as the Incarnation, through the power of the Holy Spirit, God became united with human nature through the conception of Christ in the womb of the Blessed Virgin Mary. Christ therefore is both fully divine and fully human, including possessing a human soul. It is taught that Christ's mission on earth included giving people his teachings and providing his example for them to follow as recorded in the four Gospels.[81] Jesus is believed to have remained sinless while on earth, and to have been allowed himself to be unjustly executed by Crucifixion, as sacrifice of himself to reconcile God to humanity; this reconciliation is known as the Paschal Mystery.[82] The Greek term "Christ" and the Hebrew "Messiah" both mean "anointed one", referring to the Christian belief that Jesus' death and resurrection are the fulfilment of the Old Testament's messianic prophecies.[83]

The Church teaches dogmatically that "the Holy Spirit proceeds eternally from the Father and the Son, not as from two principles but as from one single principle".[84] It holds that the Father, as the "principle without principle", is the first origin of the Spirit, but also that he, as Father of the only Son, is with the Son the single principle from which the Spirit proceeds.[85] This belief is expressed in the Filioque clause added to the Latin version of the Nicene Creed of 381, but not included in the Greek versions of the Creed that are used in Eastern Christianity.[86]

Nature of the Church[edit]

The Catholic Church teaches that it is the "one, true church"[4][87] and "the universal sacrament of salvation for the human race".[88][89] According to the Catechism, the Catholic Church is further described in the Nicene Creed as the "one, holy, catholic, and apostolic Church".[90] These are collectively known as the Four Marks of the Church. The church teaches that its founder is Jesus Christ.[91][92] The New Testament records several events considered integral to the establishment of the Catholic Church, including Jesus' activities and teaching and his appointment of the apostles as witnesses to his ministry, sacrifice and resurrection. The Great Commission, after his resurrection, instructed the apostles to continue his work. The coming of the Holy Spirit upon the apostles, in an event known as Pentecost, is seen as the beginning of the public ministry of the Catholic Church.[93] The church teaches that all duly consecrated bishops have a lineal succession from the apostles of Christ, known as apostolic succession.[94] In particular, the Bishop of Rome (the Pope), is considered the successor to the apostle Simon Peter, a position from which he derives his supremacy over the Church.[95]Catholic belief holds that the Church "is the continuing presence of Jesus on earth"[96] and that it alone possesses the full means of salvation.[97] Through the passion (suffering) of Christ leading to his crucifixion as described in the Gospels, it is said Christ made himself an oblation to God the Father in order to reconcile humanity to God;[98] the Resurrection of Jesus is said to gain for humans a possible future immortality previously denied to them because of Original Sin.[99] By reconciling with God and following Christ's words and deeds, an individual can enter the Kingdom of God.[100] The Church sees its liturgy and sacraments as perpetuating the graces achieved through Christ's sacrifice to strengthen a person's relationship with Christ and aid in overcoming sin.[9]

Judgement after death[edit]

Before his resurrection from the dead, Jesus Christ grants salvation to souls by the Harrowing of Hell. Oil on canvas, by Fra Angelico circa 1430s

Depending on the judgement rendered following death, it is believed that a soul may enter one of three states of afterlife:

- Heaven is a time of glorious union with God and a life of unspeakable joy that lasts forever.[103]

- Purgatory is a temporary condition for the purification of souls who, although saved, are not free enough from sin to enter directly into heaven.[104] Souls in purgatory may be aided in reaching heaven by the prayers of the faithful on earth and by the intercession of saints.[105]

- Final Damnation: Finally, those who persist in living in a state of mortal sin and do not repent before death subject themselves to hell, an everlasting separation from God.[106] The Church teaches that no one is condemned to hell without having freely decided to reject God.[107] No one is predestined to hell and no one can determine whether anyone else has been condemned.[108] Catholicism teaches that through God's mercy a person can repent at any point before death and be saved.[109] Some Catholic theologians have speculated that the souls of unbaptised infants who die in original sin are assigned to limbo although this is not an official doctrine of the Church.[110]

Virgin Mary and devotions[edit]

Main articles: Veneration of Mary in Roman Catholicism, Roman Catholic Mariology and Catholic devotions

Further information: Mary (mother of Jesus)

The Blessed Virgin Mary is highly regarded in the Catholic Church, proclaiming her as Mother of God, free from original sin and an intercessor.

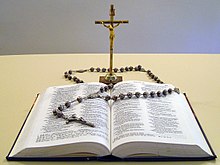

Devotions to Mary are part of Catholic piety but are distinct from the worship of God.[113] Practices include prayers and Marian art, music and architecture. Several liturgical Marian feasts are celebrated throughout the Church Year and she is honoured with many titles such as Queen of Heaven. Pope Paul VI called her Mother of the Church because, by giving birth to Christ, she is considered to be the spiritual mother to each member of the Body of Christ.[112] Because of her influential role in the life of Jesus, prayers and devotions such as the Hail Mary, the Rosary, the Salve Regina and the Memorare are common Catholic practices.[114] Pilgrimages to the sites of several Marian apparitions affirmed by the Church, such as Lourdes, Fátima, and Guadalupe,[115] are also popular Catholic devotions.[116]

Devotions are "external practices of piety" which are not part of the official liturgy of the Catholic Church but are part of the popular spiritual practices of Catholics.[117] Outside of Mariology, other devotional practices include the Stations of the Cross, the Sacred Heart of Jesus, the Holy Face of Jesus,[118] the various scapulars, novenas to various saints,[119] pilgrimages[120] and devotions to the Blessed Sacrament,[119] and the veneration of saintly images such as the santos.[121]

Liturgical worship[edit]

Main article: Catholic liturgy

Further information: Christian liturgy

The liturgy of the sacrament of the Eucharist, called the Mass in the West and Divine Liturgy or other names in the East, is the principal liturgy of the Catholic Church.[124] This is because it is considered the propitiatory sacrifice of Christ himself.[125] The most widely used is the Roman Rite, usually in its ordinary form promulgated by Paul VI in 1969, but also in its authorised extraordinary form, the Tridentine Mass as in the 1962 edition of the Roman Missal. Eastern Catholic Churches have their own rites. The liturgies of the Eucharist and the other sacraments vary from rite to rite based on differing theological emphasis.

Western rites[edit]

| Catholic Church |

|---|

| Structure of the Roman Rite Mass[126]  Roman Missal, chalice (with purificator, paten and pall), crucifix, lit candle |

| A. Introductory rites |

|

| B. Liturgy of the Word |

| C. Liturgy of the Eucharist |

See also: Eucharist in the Catholic Church

|

| D. Concluding rites |

Catholicism portal |

The 1962 edition of the Roman Missal, published a few months before the Second Vatican Council opened, was the last that presented the Mass as standardised in 1570 by Pope Pius V at the request of the Council of Trent and that is therefore known as the Tridentine Mass.[130] Pope Pius V's Roman Missal was subjected to minor revisions by Pope Clement VIII in 1604, Pope Urban VIII in 1634, Pope Pius X in 1911, Pope Pius XII in 1955, and Pope John XXIII in 1962. Each successive edition was the ordinary form of the Roman Rite Mass until superseded by a later edition. When the 1962 edition was superseded by that of Paul VI, promulgated in 1969, its continued use at first required permission from bishops;[131] but Pope Benedict XVI's 2007 motu proprio Summorum Pontificum allowed free use of it for Mass celebrated without a congregation and authorised parish priests to permit, under certain conditions, its use even at public Masses. Except for the scriptural readings, which Pope Benedict allowed to be proclaimed in the vernacular language, it is celebrated exclusively in liturgical Latin.[132]

Since 2014, clergy in the small personal ordinariates set up for groups of former Anglicans under the terms of the 2009 document Anglicanorum Coetibus[133] are permitted to use a variation of the Roman Rite called "Divine Worship" or, less formally, "Ordinariate Use",[134] which incorporates elements of the Anglican liturgy and traditions.[note 9]

In the archdiocese of Milan, with around five million Catholics the largest in Europe,[135] Mass is celebrated according to the Ambrosian Rite. Other Latin Church rites include the Mozarabic[136] and those of some religious orders.[137] These liturgical rites have an antiquity of at least 200 years before 1570, the date of Pope Pius V's Quo primum, and were thus allowed to continue.[138]

Eastern rites[edit]

An Eastern Catholic bishop of the Syro-Malabar Church holding the Mar Thoma Cross which symbolises the heritage and identity of the Saint Thomas Christians of India

The rites used by the Eastern Catholic Churches include the Byzantine Rite, in its Antiochian, Greek and Slavonic varieties; the Alexandrian Rite; the Syriac Rite; the Armenian Rite; the Maronite Rite and the Chaldean Rite. Eastern Catholic Churches have the autonomy to set the particulars of their liturgical forms and worship, within certain limits to protect the "accurate observance" of their liturgical tradition.[140] In the past some of the rites used by the Eastern Catholic Churches were subject to a degree of liturgical Latinisation. However, in recent years Eastern Catholic Churches have returned to traditional Eastern practices in accord with the Vatican II decree Orientalium Ecclesiarum.[141] Each church has its own liturgical calendar.[142]

Sacraments[edit]

Main article: Sacraments of the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church teaches that it was entrusted with seven sacraments that were instituted by Christ. The number and nature of the sacraments were defined by several ecumenical councils, most recently the Council of Trent.[143][note 10] These are Baptism, Confirmation, the Eucharist, Penance, Anointing of the Sick (formerly called Extreme Unction, one of the "Last Rites"), Holy Orders and Holy Matrimony. Sacraments are visible rituals that Catholics see as signs of God's presence and effective channels of God's grace to all those who receive them with the proper disposition (ex opere operato).[144] The Catechism of the Catholic Church categorises the sacraments into three groups, the "sacraments of Christian initiation", "sacraments of healing" and "sacraments at the service of communion and the mission of the faithful". These groups broadly reflect the stages of people's natural and spiritual lives which each sacrament is intended to serve.[145]The liturgies of the sacraments are central to the church's mission. According to the catechism:

In the liturgy of the New Covenant every liturgical action, especially the celebration of the Eucharist and the sacraments, is an encounter between Christ and the Church. The liturgical assembly derives its unity from the "communion of the Holy Spirit" who gathers the children of God into the one Body of Christ. This assembly transcends racial, cultural, social - indeed, all human affinities.[146]According to church doctrine, the sacraments of the church require the proper form, matter, and intent to be validly celebrated.[147] In addition, the Canon Laws for both the Latin Church and the Eastern Catholic Church govern who may licitly celebrate certain sacraments, as well as strict rules about who may receive the sacraments.[148] Notably, because the Church teaches that Christ is present in the Eucharist,[130] those who are conscious of being in a state of mortal sin are forbidden to receive the sacrament until they have received absolution through the sacrament of Reconciliation (Penance).[149] Catholics are normally obliged to abstain from eating for at least an hour before receiving the sacrament.[149] Non-Catholics such are ordinarily prohibitted from receiving the Eucharist as well.[148][150]

Catholics, even if they were in danger of death and unable to approach a Catholic minister, may not ask for the sacraments of the Eucharist, penance or anointing of the sick from someone, such as a Protestant minister, who is not known to be validly ordained in line with Catholic teaching on ordination.[151][152] Likewise, even in grave and pressing need, Catholic ministers may not administer these sacraments to those who do not manifest Catholic faith in the sacrament. In relation to the churches of Eastern Christianity not in communion with the Holy See, the Catholic Church is less restrictive, declaring that "a certain communion in sacris, and so in the Eucharist, given suitable circumstances and the approval of Church authority, is not merely possible but is encouraged."[153]

Sacraments of Christian initiation[edit]

Main article: Sacraments of Initiation

Baptism[edit]

As viewed by the Catholic Church, Baptism is the first of three sacraments of initiation as a Christian.[154] It washes away all sins, both original sin and personal actual sins.[155] It makes a person a member of the Church.[156] As a gratuitous gift of God that requires no merit on the part of the person who is baptised, it is conferred even on children,[157] who, though they have no personal sins, need it on account of original sin.[158] If a new-born child is in a danger of death, anyone—be it a doctor, a nurse, or a parent—may baptise the child.[159] Baptism marks a person permanently and cannot be repeated.[160] The Catholic Church recognises as valid baptisms conferred even by people who are not Catholics or Christians, provided that they intend to baptise ("to do what the Church does when she baptises") and that they use the Trinitarian baptismal formula.[161]Confirmation[edit]

The Catholic Church sees the sacrament of confirmation as required to complete the grace given in baptism.[162] When adults are baptised, confirmation is normally given immediately afterwards,[163] a practice followed even with newly baptised infants in the Eastern Catholic Churches.[164] In the West confirmation of children is delayed until they are old enough to understand or at the bishop's discretion.[165] In Western Christianity, particularly Catholicism, the sacrament is called confirmation, because it confirms and strengthens the grace of baptism; in the Eastern Churches, it is called chrismation, because the essential rite is the anointing of the person with chrism,[166] a mixture of olive oil and some perfumed substance, usually balsam, blessed by a bishop.[166][167] Those who receive confirmation must be in a state of grace, which for those who have reached the age of reason means that they should first be cleansed spiritually by the sacrament of Penance; they should also have the intention of receiving the sacrament, and be prepared to show in their lives that they are Christians.[168]

Pope Benedict XVI celebrates the Eucharist at the canonisation of Frei Galvão in São Paulo, Brazil on 11 May 2007

Eucharist[edit]

For Catholics, the Eucharist is the sacrament which completes Christian initiation. It is described as "the source and summit of the Christian life".[169] The ceremony in which a Catholic first receives the Eucharist is known as First Communion.[170]The Eucharistic celebration, also called the Mass or Divine liturgy, includes prayers and scriptural readings, as well as an offering of bread and wine, which are brought to the altar and consecrated by the priest to become the body and the blood of Jesus Christ, a change called transubstantiation.[171][note 11] The words of consecration reflect the words spoken by Jesus during the Last Supper, where Christ offered his body and blood to his Apostles the night before his crucifixion. The sacrament re-presents (makes present) the sacrifice of Jesus on the cross,[172] and perpetuates it. Christ's death and resurrection gives grace through the sacrament that unites the faithful with Christ and one another, remits venial sin, and aids against committing moral sin (though mortal sin itself is forgiven through the sacrament of penance).[173]

Sacraments of healing[edit]

The two sacraments of healing are the Sacrament of Penance and Anointing of the Sick.Penance[edit]

The Sacrament of Penance (also called Reconciliation, Forgiveness, Confession, and Conversion[174]) exists for the conversion of those who, after baptism, separate themselves from Christ by sin.[175] Essential to this sacrament are acts both by the sinner (examination of conscience, contrition with a determination not to sin again, confession to a priest, and performance of some act to repair the damage caused by sin) and by the priest (determination of the act of reparation to be performed and absolution).[176] Serious sins (mortal sins) must be confessed within at most a year and always before receiving Holy Communion, while confession of venial sins also is recommended.[177] The priest is bound under the severest penalties to maintain the "seal of confession", absolute secrecy about any sins revealed to him in confession.[178]Anointing of the Sick[edit]

While chrism is used only for the three sacraments that cannot be repeated, a different oil is used by a priest or bishop to bless a Catholic who, because of illness or old age, has begun to be in danger of death.[179] This sacrament, known as Anointing of the Sick, is believed to give comfort, peace, courage and, if the sick person is unable to make a confession, even forgiveness of sins.[180]The sacrament is also referred to as Unction, and in the past as Extreme Unction, and it is one of the three sacraments that constitute the last rites, together with Penance and Viaticum (Eucharist).[181]

Sacraments at the service of communion[edit]

According to the Catechism of the Catholic Church there are two sacraments of communion directed towards the salvation of others: priesthood and marriage.[182] Within the general vocation to be a Christian, these two sacraments consecrate to specific mission or vocation among the people of God. Men receive the holy orders to feed the Church by the word and grace. Spouses marry so that their love may be fortified to fulfill duties of their state.[183]Ordination[edit]

The sacrament of Holy Orders consecrates and deputes some Christians to serve the whole body as members of three degrees or orders: episcopate (bishops), presbyterate (priests) and diaconate (deacons).[184][185] The Church has defined rules on who may be ordained into the clergy. In the Latin Rite, the priesthood and diaconate are generally restricted to celibate men.[186][187] Men who are already married may be ordained in the Eastern Catholic Churches in most countries,[188] and the personal ordinariates and may become deacons even in the Western Church[186][187] (see Clerical marriage). But after becoming a Roman Catholic priest, a man may not marry (see Clerical celibacy) unless he is formally laicised.All clergy, whether deacons, priests or bishops, may preach, teach, baptise, witness marriages and conduct funeral liturgies.[189] Only bishops and priests can administer the sacraments of the Eucharist, Reconciliation (Penance) and Anointing of the Sick.[190][191] Only bishops can administer the sacrament of Holy Orders, which ordains someone into the clergy.[192]

Matrimony[edit]

Main article: Sacrament of marriage

See also: Catholic Church § Sexual morality

The Catholic Church teaches that marriage is a social and spiritual bond between a man and a woman, ordered towards the good of the spouses and procreation of children; according to Catholic teachings on sexual morality, it is the only appropriate context for sexual activity. A Catholic marriage, or any marriage between baptised individuals of any Christian denomination, is viewed as a sacrament. A sacramental marriage, once consummated, cannot be dissolved except by death.[193][note 12] The Church recognises certain conditions, such as freedom of consent, as required for any marriage to be valid; In addition, the Church sets specific rules and norms, known as canonical form, that Catholics must follow.[194]The church does not recognise divorce as ending a valid marriage and allows state recognised divorce only as a means of protecting the property and well being of the spouses and any children. However, failure to observe the Church's regulations, as well as defects applicable to all marriages, may be grounds for a church declaration of the invalidity of a marriage, a declaration usually referred to as an annulment.[195] Remarriage following a divorce is not permitted unless the prior marriage was declared invalid.[195]

Social and cultural issues[edit]

Main articles: Catholic social teaching, Catholicism and sexuality and Criticism of the Catholic Church

Catholic teaching regarding most social issues involves maintaining bodily integrity. Catholic social teaching, reflecting the concern Jesus showed for the impoverished, places a heavy emphasis on the corporal works of mercy and the spiritual works of mercy, namely the support and concern for the sick, the poor and the afflicted.[196][197] Church teaching calls for a preferential option for the poor while canon law prescribes that "The Christian faithful are also obliged to promote social justice and, mindful of the precept of the Lord, to assist the poor."[198]Catholic teaching regarding sexuality calls for a practice of chastity, with a focus on maintaining the spiritual and bodily integrity of the human person. Marriage is considered the only appropriate context for sexual activity.[199] Church teachings about sexuality have become an issue of increasing controversy, especially after the close of the Second Vatican Council, due to changing cultural attitudes in the Western world described as the sexual revolution.

Sexual morality[edit]

See also: Catholic Church § Sacrament of marriage

Main articles: Catholic teachings on sexual morality and Marriage (Catholic Church)

Sexuality is considered integral to a person's identity and ability to form lasting relationships. The Catholic Church calls all members to live chastely according to their state in life. Chastity includes temperance, self-mastery, personal and cultural growth, and grace. It requires refraining from lust, masturbation, fornication, pornography, prostitution and, especially, rape. Chastity for those who are not married requires living in continence, abstaining from sexual activity; those who are married are called to conjugal chastity.[200] In the church's teaching, sexual activity is reserved to married couples, whether in a sacramental marriage among Christians, or in a natural marriage among those who are unbaptised. Even in romantic relationships, particularly engagement to marriage, partners are called to practice continence, in order to test mutual respect and fidelity.[201]Chastity in marriage requires in particular conjugal fidelity and protecting the fecundity of marriage. The couple must foster trust and honesty as well as spiritual and physical intimacy. Sexual activity must always be open to the possibility of life;[202] the church calls this the procreative significance. It must likewise always bring a couple together in love; the church calls this the unitive significance.[203] Contraception and certain other sexual practices are not permitted, although natural family planning methods are permitted to provide healthy spacing between births, or to postpone children for a just reason.[204]

Divorce and declarations of nullity[edit]

Main article: Annulment (Catholic Church)

Further information: Divorce law by country

Canon law makes no provision for divorce among baptised individuals, as a valid sacramental marriage is considered to be a lifelong bond.[205] However, a declaration of nullity may be granted when proof is produced that essential conditions for contracting a valid marriage were absent from the beginning — in other words, that the marriage was not valid due to some impediment. A declaration of nullity, commonly called an annulment, is a judgement on the part of an ecclesiastical tribunal determining that a marriage was invalidly attempted.[206] In addition, marriages among unbaptised individuals may be dissolved with papal permission under certain situations, such as a desire to marry a Catholic, under Pauline or Petrine privilege.[207][208] An attempt at remarriage following divorce without a declaration of nullity places "the remarried spouse [...] in a situation of public and permanent adultery". An innocent spouse who lives in continence following divorce, or couples who live in continence following a civil divorce for a grave cause, do not sin.[209]Worldwide, diocesan tribunals completed over 49000 cases for nullity of marriage in 2006. Over the past 30 years about 55 to 70% of annulments have occurred in the United States. The growth in annulments has been substantial; in the United States, 27,000 marriages were annulled in 2006, compared to 338 in 1968. However, approximately 200,000 married Catholics in the United States divorce each year; 10 million total as of 2006.[210][note 13] Divorce is increasing in some predominantly Catholic countries in Europe.[211] In some predominantly Catholic countries, it is only in recent years that divorce was introduced (i.e. Italy (1970), Portugal (1975), Brazil (1977), Spain (1981), Ireland (1996), Chile (2004) and Malta (2011), while the Philippines and the Vatican City have no procedure for divorce (the Philippines does, however, allow divorce for Muslims).

Contraception[edit]

Main article: Christian views on contraception § Catholicism

The church teaches that sexual intercourse should only take place between a married man and woman, and should be without the use of birth control or contraception. In his encyclical Humanae vitae[212] (1968), Pope Paul VI firmly rejected all contraception, thus contradicting dissenters in the Church that saw the birth control pill as an ethically justifiable method of contraception, though he permitted the regulation of births by means of natural family planning. This teaching was continued especially by John Paul II in his encyclical Evangelium Vitae, where he clarified the Church's position on contraception, abortion and euthanasia by condemning them as part of a "culture of death" and calling instead for a "culture of life".[213]Many Western Catholics have voiced significant disagreement with the Church's teaching on contraception.[214] Catholics for Choice stated in 1998 that 96% of U.S. Catholic women had used contraceptives at some point in their lives and that 72% of Catholics believed that one could be a good Catholic without obeying the Church's teaching on birth control.[215] Use of natural family planning methods among United States Catholics purportedly is low, although the number cannot be known with certainty.[note 14] As Catholic health providers are among the largest providers of services to patients with HIV/AIDS worldwide, there is significant controversy within and outside the church regarding the use of condoms as a means of limiting new infections, as condom use ordinarily constitutes prohibited contraceptive use.[216]

Similarly, the Catholic Church opposes in vitro fertilization (IVF), saying that the artificial process replaces the love between a husband and wife.[217] In addition, it opposes IVF because it might cause disposal of embryos; Catholics believe an embryo is an individual with a soul who must be treated as such.[218] For this reason, the church also opposes abortion.[219]

Homosexuality[edit]

Main article: Homosexuality and Roman Catholicism

The Catholic Church also teaches that "homosexual acts" are "contrary to the natural law", and thus sinful, but that persons experiencing homosexual tendencies must be accorded respect and dignity.[220] According to the Catechism of the Catholic Church,The number of men and women who have deep-seated homosexual tendencies is not negligible. This inclination, which is objectively disordered, constitutes for most of them a trial. They must be accepted with respect, compassion, and sensitivity. Every sign of unjust discrimination in their regard should be avoided….This part of the Catechism was quoted by Pope Francis in a 2013 press interview in which he remarked, when asked about an individual:

Homosexual persons are called to chastity. By the virtues of self-mastery that teach them inner freedom, at times by the support of disinterested friendship, by prayer and sacramental grace, they can and should gradually and resolutely approach Christian perfection.[221]

I think that when you encounter a person like this [the individual he was asked about], you must make a distinction between the fact of a person being gay from the fact of being a lobby, because lobbies, all are not good. That is bad. If a person is gay and seeks the Lord and has good will, well who am I to judge them?[222]This remark and others made in the same interview were seen as a change in the tone, but not in the substance of the teaching of the Church,[223] which includes opposition to same-sex marriage.[224] Certain dissenting Catholic groups oppose the position of the Catholic Church and seek to change it.[225]

Social services[edit]

Main articles: Catholic Church and health care and Catholic education

Blessed Mother Teresa of Calcutta advocated for the sick, the poor and the needy by practising the acts of corporal works of mercy.

Religious institutes for women have played a particularly prominent role in the provision of health and education services,[228] as with orders such as the Sisters of Mercy, Little Sisters of the Poor, the Missionaries of Charity, the Sisters of St. Joseph of the Sacred Heart, the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament and the Daughters of Charity of Saint Vincent de Paul.[229] The Catholic nun Mother Teresa of Calcutta, India, founder of the Sisters of Mercy, was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1979 for her humanitarian work among India's poor.[230] Bishop Carlos Filipe Ximenes Belo won the same award in 1996 for "work towards a just and peaceful solution to the conflict in East Timor".[231]

The Church is also actively engaged in international aid and development through organisations such as Catholic Relief Services, Caritas International, Aid to the Church in Need, refugee advocacy groups such as the Jesuit Refugee Service and community aid groups such as the Saint Vincent de Paul Society.[232]

Women and ordination[edit]

Main articles: Catholic Church doctrine on the ordination of women and Catholic Church and women

Women religious engage in a variety of occupations, from contemplative prayer, to teaching, to providing health care, to working as missionaries.[68][228] While Holy Orders are reserved for men, Catholic women have played diverse roles in the life of the church, with religious institutes providing a formal space for their participation and convents providing spaces for their self-government, prayer and influence through many centuries. Religious sisters and nuns have been extensively involved in developing and running the Church's worldwide health and education service networks.[233]Efforts in support of the ordination of women led to several rulings by the Roman Curia or Popes against the proposal, as in Declaration on the Question of the Admission of Women to the Ministerial Priesthood (1976), Mulieris Dignitatem (1988) and Ordinatio Sacerdotalis (1994). According to the latest ruling, found in Ordinatio Sacerdotalis, Pope John Paul II affirmed that the Catholic Church "does not consider herself authorized to admit women to priestly ordination."[234] In defiance of these rulings, opposition groups such as Roman Catholic Womenpriests have performed ceremonies they affirm as sacramental ordinations (with, reputedly, an ordaining male Catholic bishop in the first few instances) which, according to canon law, are both illicit and invalid and considered mere simulations[235] of the sacrament of ordination.[236][note 15] The Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith responded by issuing a statement clarifying that any Catholic bishops involved in ordination ceremonies for women, as well as the women themselves if they were Catholic, would automatically receive the penalty of excommunication (latae sententiae, literally "with the sentence already applied", i.e. automatically), citing canon 1378 of canon law and other church laws.[237]

Sex abuse cases[edit]

Main article: Catholic sex abuse cases

In the 1990s and 2000s, the issue of sexual abuse of minors by Catholic clergy and other church members became the subject of civil litigation, criminal prosecution, media coverage and public debate in countries around the world. The Catholic Church was criticised for its handling of abuse complaints when it became known that some bishops had shielded accused priests, transferring them to other pastoral assignments where some continued to commit sexual offences.In response to the scandal, formal procedures have been established to help prevent abuse, encourage the reporting of any abuse that occurs and to handle such reports promptly, although groups representing victims have disputed their effectiveness.[238] In 2014, Pope Francis instituted the Pontifical Commission for the Protection of Minors for the safeguarding of minors.[239]

History[edit]

Main article: History of the Catholic Church

Further information: Early history of Christianity, Historiography of early Christianity and Apostolic Age

This fresco (1481–82) by Pietro Perugino in the Sistine Chapel shows Jesus giving the keys of heaven to Saint Peter.

In the 7th and 8th centuries, expanding Muslim conquests following the advent of Islam led to an Arab domination of the Mediterranean that severed political connections between that area and northern Europe, and weakened cultural connections between Rome and the Byzantine Empire. Conflicts involving authority in the church, particularly the authority of the Bishop of Rome finally culminated in the East–West Schism in the 11th century, splitting the Church into the Catholic and Orthodox Churches. Earlier splits within the Church occurred after the Council of Ephesus (431) and the Council of Chalcedon (451). However, a few Eastern Churches remained in communion with Rome, and portions of some others established communion in the 1400s and later, forming what are called the Eastern Catholic Churches.

Early monasteries throughout Europe helped preserve Greek and Roman classical civilisation. The Church eventually became the dominant influence in Western civilisation into the modern age. Many Renaissance figures were sponsored by the church. The 16th century, however, began to see challenges to the Church, in particular to its religious authority, by figures in the Protestant Reformation, as well as in the 17th century by secular intellectuals in the Enlightenment. Concurrently, Spanish and Portuguese explorers and missionaries spread the Church's influence through Africa, Asia, and the New World.

In 1870, the First Vatican Council declared the dogma of papal infallibility. Also in 1870, the Kingdom of Italy annexed the city of Rome, the last portion of the Papal States to be incorporated in the new nation. In the 20th century, the church endured a massive backlash at the hands of anti-clerical governments around the world, including Mexico and Spain, where thousands of clerics and laypersons were persecuted or executed. During the Second World War, the Church condemned Nazism, and protected hundreds of thousands of Jews from the Holocaust; its efforts, however, have been criticised as potentially inadequate. After the war, freedom of religion was severely restricted in the Communist countries newly aligned with the Soviet Union, several of which had large Catholic populations.

In the 1960s, the Second Vatican Council led to several controversial reforms of the church liturgy and practices, an effort descried as "opening the windows" by defenders, but leading to harsh criticism in several conservative circles. In the face of increased criticism from both within and without, the Church has upheld or reaffirmed at various times controversial doctrinal positions regarding sexuality and gender, including limiting clergy to males, and moral exhortations against abortion, contraception, sexual activity outside of marriage, remarriage following divorce without annulment, and against homosexual marriage.

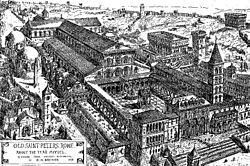

Apostolic era and papacy[edit]

The New Testament, in particular the Gospels, records Jesus' activities and teaching, his appointment of the twelve Apostles and his Great Commission of the Apostles, instructing them to continue his work.[92][240] The book Acts of Apostles, tells of the founding of the Christian church and the spread of its message to the Roman empire.[241] The Catholic Church teaches that its public ministry began on Pentecost, occurring fifty days following the date Christ is believed to have resurrected.[93] At Pentecost, the Apostles are believed to have received the Holy Spirit, preparing them for their mission in leading the church.[242][243] The Catholic Church teaches that the college of bishops, led by the Bishop of Rome are the successors to the Apostles.[244]In the account of the Confession of Peter found in the Gospel of Matthew, Christ designates Peter as the "rock" upon which Christ's church will be built.[245][246] The Catholic Church considers the Bishop of Rome, the Pope, to be the successor to Saint Peter.[247] Some scholars state Peter was the first Bishop of Rome.[248][note 16] Others say that the institution of the papacy is not dependent on the idea that Peter was Bishop of Rome or even on his ever having been in Rome.[249] Many scholars hold that a church structure of plural presbyters/bishops persisted in Rome until the mid-2nd century, when the structure of a single bishop and plural presbyters was adopted,[250] and that later writers retrospectively applied the term "bishop of Rome" to the most prominent members of the clergy in the earlier period and also to Peter himself.[250] On this basis, Oscar Cullmann,[251] Henry Chadwick,[252] and Bart D. Ehrman[253] question whether there was a formal link between Peter and the modern papacy. Raymond E. Brown also says that it is anachronistic to speak of Peter in terms of local bishop of Rome, but that Christians of that period would have looked on Peter as having "roles that would contribute in an essential way to the development of the role of the papacy in the subsequent church". These roles, Brown says, "contributed enormously to seeing the bishop of Rome, the bishop of the city where Peter died, and where Paul witnessed to the truth of Christ, as the successor of Peter in care for the church universal".[250]

Antiquity and Roman Empire[edit]

Main articles: Early centers of Christianity and List of Christian heresies

Conditions in the Roman Empire facilitated the spread of new ideas. The empire's well-defined network of roads and waterways facilitated travel, and the Pax Romana made travelling safe. The empire encouraged the spread of a common culture with Greek roots, which allowed ideas to be more easily expressed and understood.[254]Unlike most religions in the Roman Empire, however, Christianity required its adherents to renounce all other gods, a practice adopted from Judaism (see Idolatry). The Christians' refusal to join pagan celebrations meant they were unable to participate in much of public life, which caused non-Christians—including government authorities—to fear that the Christians were angering the gods and thereby threatening the peace and prosperity of the Empire. The resulting persecutions were a defining feature of Christian self-understanding until Christianity was legalised in the 4th century.[255]

Most of the Germanic tribes who in the following centuries invaded the Roman Empire had adopted Christianity in its Arian form, which the Catholic Church declared heretical.[265] The resulting religious discord between Germanic rulers and Catholic subjects[266] was avoided when, in 497, Clovis I, the Frankish ruler, converted to orthodox Catholicism, allying himself with the papacy and the monasteries.[267] The Visigoths in Spain followed his lead in 589,[268] and the Lombards in Italy in the course of the 7th century.[269]

Western Christianity, particularly through its monasteries, was a major factor in preserving classical civilisation, with its art (see Illuminated manuscript) and literacy.[270][271] Through his Rule, Benedict of Nursia (c.480–543), one of the founders of Western monasticism, exerted an enormous influence on European culture through the appropriation of the monastic spiritual heritage of the early Church and, with the spread of the Benedictine tradition, through the preservation and transmission of ancient culture. During this period, monastic Ireland became a centre of learning and early Irish missionaries such as St Columbanus and St Columba spread Christianity and established monasteries across continental Europe.[1]

The massive Islamic invasions of the mid-7th century began a long struggle between Christianity and Islam throughout the Mediterranean Basin. The Byzantine Empire soon lost the lands of the eastern patriarchates of Jerusalem, Alexandria and Antioch and was reduced to that of Constantinople, the empire's capital. As a result of Islamic domination of the Mediterranean, the Frankish state, centred away from that sea, was able to evolve as the dominant power that shaped the Western Europe of the Middle Ages.[272] The battles of Toulouse and Poitiers halted the Islamic advance in the West. Two or three decades later, in 751, the Byzantine Empire lost to the Lombards the city of Ravenna from which it governed the small fragments of Italy, including Rome, that acknowledged its sovereignty. The fall of Ravenna meant that confirmation by a no longer existent exarch was not asked for the election in 752 of Pope Stephen II and that the papacy was forced to look elsewhere for a civil power to protect it.[273] In 754, at the urgent request of Pope Stephen, the Frankish king Pepin the Short conquered the Lombards. He then gifted the lands of the former exarchate to the pope, thus initiating the Papal States. Rome and the Byzantine East would delve into further conflict during the Photian schism of the 860s, when Photius criticized the Latin west of adding of the filioque clause after being excommunicated by Nicholas I. Though the schism was reconciled, unresolved issues would lead to further division.[274]

Medieval and Renaissance periods[edit]

The Catholic Church was the dominant influence on Western civilisation from late antiquity to the dawn of the modern age.[2] It was the primary sponsor of Romanesque, Gothic, Renaissance, Mannerist and Baroque styles in art, architecture and music.[275] Renaissance figures such as Raphael, Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, Botticelli, Fra Angelico, Tintoretto, Titian, Bernini and Caravaggio are examples of the numerous visual artists sponsored by the Church.[276]In the eleventh century, the efforts of Hildebrand of Sovana led to the creation of the College of Cardinals to elect new Popes, starting with Pope Alexander II in the papal election of 1061. When Alexander II died, Hildebrand was elected to succeed him, as Pope Gregory VII. The basic election system of the College of Cardinals which Gregory VII helped establish has continued to function into the twenty-first century. Pope Gregory VII further initiated the Gregorian Reforms regarding the independence of the clergy from secular authority. This led to the Investiture Controversy between the church and the Holy Roman Emperors, over which had the authority to appoint bishops and Popes.[277][278]

In 1095, Byzantine emperor Alexius I appealed to Pope Urban II for help against renewed Muslim invasions in the Byzantine–Seljuk Wars,[279] which caused Urban to launch the First Crusade aimed at aiding the Byzantine Empire and returning the Holy Land to Christian control.[280] In the 11th century, strained relations between the primarily Greek church and the Latin Church separated them in the East–West Schism, partially due to conflicts over papal authority. The Fourth Crusade and the sacking of Constantinople by renegade crusaders proved the final breach.[281]

The Renaissance period was a golden age for Roman Catholic art. Pictured: the Sistine Chapel ceiling.

A growing sense of church-state conflicts marked the 14th century. To escape instability in Rome, Clement V in 1309 became the first of seven popes to reside in the fortified city of Avignon in southern France[284] during a period known as the Avignon Papacy. The Avignon Papacy ended in 1376 when the Pope returned to Rome,[285] but was followed in 1378 by the 38-year-long Western schism with claimants to the papacy in Rome, Avignon and (after 1409) Pisa.[285] The matter was finally resolved in 1417 at the Council of Constance where the cardinals called upon all three claimants to the papal throne to resign, and held a new election naming Martin V pope.[286]

In 1438, the Council of Florence convened, which featured a strong dialogue focussed on understanding the theological differences between the East and West, with the hope of reuniting the Catholic and Orthodox churches.[287] Several eastern churches reunited, forming the Eastern Catholic Churches.[288]

Age of discovery[edit]

Main article: Catholic Church and the Age of Discovery

The Age of Discovery beginning in the 15th century saw the expansion of Western Europe's political and cultural influence worldwide. Because of the prominent role the strongly Catholic nations of Spain and Portugal played in Western Colonialism, Catholicism was spread to the Americas, Asia and Oceania by explorers, conquistadors, and missionaries, as well as by the transformation of societies through the socio-political mechanisms of colonial rule. Pope Alexander VI had awarded colonial rights over most of the newly discovered lands to Spain and Portugal[289] and the ensuing patronato system allowed state authorities, not the Vatican, to control all clerical appointments in the new colonies.[290] In 1521 the Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan made the first Catholic converts in the Philippines.[291] Elsewhere, Portuguese missionaries under the Spanish Jesuit Francis Xavier evangelised in India, China, and Japan.[292]Reformation[edit]

Main article: Protestant Reformation

The Reformation led to clashes between the Protestant Schmalkaldic League and the Catholic Emperor Charles V and his allies. The first nine-year war ended in 1555 with the Peace of Augsburg but continued tensions produced a far graver conflict—the Thirty Years' War—which broke out in 1618.[297] In France, a series of conflicts termed the French Wars of Religion was fought from 1562 to 1598 between the Huguenots (French Calvinists) and the forces of the French Catholic League. A series of popes sided with and became financial supporters of the Catholic League.[298] This ended under Pope Clement VIII, who hesitantly accepted King Henry IV's 1598 Edict of Nantes, which granted civil and religious toleration to French Protestants.[297][298]

The Council of Trent (1545–1563) became the driving force behind the Counter-Reformation in response to the Protestant movement. Doctrinally, it reaffirmed central Catholic teachings such as transubstantiation and the requirement for love and hope as well as faith to attain salvation.[299] In subsequent centuries, Catholicism spread widely across the world despite experiencing a reduction in its hold on European populations due to the growth of religious scepticism during and after the Enlightenment.[300]

Enlightenment and modern period[edit]

In 1854 Pope Pius IX, with the support of the overwhelming majority of Roman Catholic bishops, whom he had consulted from 1851 to 1853, proclaimed the Immaculate Conception as a dogma.[305] In 1870, the First Vatican Council affirmed the doctrine of papal infallibility when exercised in specifically defined pronouncements.[306][307] Controversy over this and other issues resulted in a breakaway movement called the Old Catholic Church.[308]

Italian unification of the 1860s incorporated the Papal States, including Rome itself from 1870, into the Kingdom of Italy, thus ending the papacy's millennial temporal power. The pope rejected the Italian Law of Guarantees, which granted him special privileges, and to avoid placing himself in visible subjection to the Italian authorities remained a "prisoner in the Vatican".[309] This stand-off, which was spoken of as the Roman Question, was resolved by the 1929 Lateran Treaties, whereby the Holy See acknowledged Italian sovereignty over the former Papal States and Italy recognised papal sovereignty over Vatican City as a new sovereign and independent state.[310]

Twentieth century[edit]

A number of anti-clerical governments emerged in the twentieth century.The 1926 Calles Law separating church and state in Mexico led to the Cristero War[311] in which over 3,000 priests were exiled or assassinated,[312] churches desecrated, services mocked, nuns raped and captured priests shot.[311] Following the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution, persecution of the Church and Catholics in the Soviet Union continued into the 1930s with the execution and exiling of clerics, monks and laymen, the confiscation of religious implements and closure of churches.[313][314] In the 1936–39 Spanish Civil War, the Catholic hierarchy allied itself with Franco's Nationalists against the Popular Front government,[315] citing Republican violence against the Church.[316][317] Pope Pius XI referred to these three countries as a "terrible triangle".[318][319]

After violations of the 1933 Reichskonkordat between the Church and Nazi Germany, Pope Pius XI issued the 1937 encyclical Mit brennender Sorge which publicly condemned the Nazis' persecution of the Church and their ideology of neopaganism and racial superiority.[320][321][322] The Church condemned the 1939 invasion of Poland and subsequent 1940 Nazi invasions.[323] Thousands of Catholic priests, nuns and brothers were imprisoned and murdered throughout the areas occupied by the Nazis, including Saints Maximilian Kolbe and Edith Stein.[324] While Pope Pius XII has been credited with helping to save hundreds of thousands of Jews in the Holocaust,[325][326] the Church has also been accused of encouraging centuries of antisemitism[327] and not doing enough to stop Nazi atrocities.[328]

Postwar Communist governments in Eastern Europe severely restricted religious freedoms.[329] Although some priests and religious collaborated with Communist regimes,[330] many were imprisoned, deported or executed and the Church was an important player in the fall of communism in Europe.[331] In 1949, Communist victory in the Chinese Civil War led to the expulsion of all foreign missionaries.[332] The new government also created the Patriotic Church whose unilaterally appointed bishops were initially rejected by Rome before many of them were accepted.[333] In the 1960s, the Cultural Revolution saw the closure of all religious establishments. When Chinese churches eventually reopened, they remained under the control of the Patriotic Church. Many Catholic pastors and priests continued to be sent to prison for refusing to renounce allegiance to Rome.[334]

Second Vatican Council[edit]

Main articles: Post Vatican II history of the Catholic Church and Spirit of Vatican II

See also: Catholic Church § contraception

The Second Vatican Council in the 1960s introduced the most significant changes to Catholic practices since the Council of Trent four centuries before.[335] Initiated by Pope John XXIII, this ecumenical council modernised the practices of the Catholic Church, allowing the Mass to be said in the vernacular (local language) and encouraging "fully conscious, and active participation in liturgical celebrations".[336] It intended to engage the Church more closely with the present world (aggiornamento), which was described by its advocates as an "opening of the windows".[337] In addition to changes in the liturgy, it led to changes to the Church's approach to ecumenism,[338] and a call to improved relations with non-Christian religions, especially Judaism, in its document Nostra aetate.[339]The council, however, generated significant controversy in implementing its reforms: proponents of the "Spirit of Vatican II" such as Swiss theologian Hans Küng said that Vatican II had "not gone far enough" to change church policies.[340] Traditionalist Catholics, such as Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre, however, strongly criticised the council, arguing that its liturgical reforms led "to the destruction of the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass and the sacraments", among other issues.[341] Several teachings of the Catholic Church came under increased scrutiny both concurrent with and following the council; among those teachings was the church's teaching regarding the immorality of contraception. The recent introduction of hormonal contraception (including "the pill"), which were believed by some to be morally different than previous methods, prompted John XXIII to form a committee to advise him of the moral and theological issues with the new method.[342][343] Paul VI later expanded the committee's scope to freely examine all methods, and the committee's unreleased final report was rumoured to suggest permitting at least some methods of contraception. Paul did not agree with the arguments presented, and eventually issued Humanae vitae, saying it upheld the constant teaching of the church against contraception, expressly including hormonal methods as prohibited.[note 17] A large negative response to this document followed its release.[344]

John Paul II[edit]

John Paul sought to evangelise an increasingly secular world. He instituted World Youth Day as a "worldwide encounter with the Pope" for young people which is now held every two to three years.[347] He travelled more than any other Pope, visiting 129 countries,[348] and used television and radio as means of spreading the Church's teachings. He also emphasised the dignity of work and natural rights of labors to have fair wages and safe conditions in Laborem exercens,[349] and also emphasised several church teachings, including moral exhortations against abortion, euthanasia, and against widespread use of the death penalty, in Evangelium Vitae.[350]

Twenty-first century[edit]

In 2005, following the death of John Paul II, Pope Benedict XVI was elected. Originally from Germany, he served as head of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith under John Paul. He was known for upholding traditional Christian values as a means to ward off secularisation,[351] and for liberalising use of the Tridentine Mass as found in the Roman Missal of 1962.[352] In 2012, the 50th anniversary of Vatican II, an assembly of the Synod of Bishops to discuss re-evangelising lapsed Catholics in the developed world.[353] Benedict resigned due to advance age in 2013, the first Pope to do so in hundreds of years.[354]Pope Francis succeeded Benedict in 2013. He was warmly received by many, although he drew concerns from some Catholics and political conservatives. In 2014, the first of two assemblies of the Synod of Bishops addressed the church's ministry towards families and marriages. Particular media attention focussed on the proposed wording of an interim document addressing Catholics in "irregular" relationships, such as Catholics who divorced and remarried outside of the church without a declaration of nullity. The first of the two, the Third Extraordinary General Assembly of the Synod of Bishops, ran from 5 to 19 October 2014.[355][356]